The top three things you need in the wilderness are food, water, and shelter. If you haven’t heard of the Rule of Threes, I highly suggest you check it out, and if you’re new to hiking or backpacking, there are a number of suggestions you should consider when it comes to finding clean water on the trail. That’s why I’ve put together this simple backpacker’s guide to safe water filtration!

This guide to safe water filtration focuses on five major topics: why water filtration is important, how much water you should have at any one time, the best places to find clean water on the trail, several ways to guarantee clean water, and the possible negatives of NOT filtering your water on the trail. I hope you find the information concise and useful!

Article Overview

Why Is Safe Water Filtration Important?

Many of this country’s earliest hikers and well-known vagabonds, such as John Muir and Edward Abbey, might scoff at the idea of water filtration. These men never thought twice about drinking straight from creeks, streams, and rivers. But today’s wilderness is a bit different from the wilderness of 50 or 100 years ago.

Many streams, creeks, and rivers contain trace amounts of bacteria. These bacteria often exist in the form of Giardia Lamblia, Cryptosporidium, and E.coli. Generally, wilderness areas with higher concentrations of human and pack animal (sheep and cattle, primarily) activity are more likely to have more bacteria in the water.

So, why is water filtration is important? While some studies have shown that water filtration doesn’t guarantee you’ll be at a lower risk of getting sick from these bacteria, I tend to air on the side of caution. It’s better to seek cleaner water sources and filter them than to rely on mere luck when it comes to your health in the backcountry.

How Much Water Should You Have?

Before we discuss finding and filtering water, it’s important to touch on just how much water you should have on your person at any one time on the trail. While this can depend on the region you’re hiking in, my first recommendation is that you never let yourself get to a point where you’re completely out of water if you’re not sure how far it is to the next water source.

In other words, if you’re hiking in a very arid, desert-like environment, you’ll want plenty of capacity to stock up when water is available. If you’re hitting the trail in the high Sierras in the springtime, on the other hand, you’ll likely be encountering at least one lake or stream to filter water on a daily basis.

Now to how much you should carry at a time. The standard Nalgene bottle offers one liter of capacity. Many packs have two water bottle pockets on either side. This means two liters of capacity before considering whether your pack also has an internal hydration bladder.

My recommendation is that you keep at least one liter of water on you at all times. Although suggested water intake can vary depending on height, weight, age, activity level, and a number of other factors, The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine recommend that adults consume anywhere between 2.5 and 4 liters of water every day.

Many hikers will find that this recommendation may even be a bit on the low side, but from personal experience, I’ve made overnight and multi-day trips work with two, one-liter Nalgenes of total water capacity. Granted, most of my hiking is done in areas that offer superior access to water sources.

Where Can You Find Clean Water On The Trail?

The answer to this question depends on exactly where you’re hiking. For years, I prioritized moving water over stagnant ponds or even larger lakes up in the high Sierras. My theory was pretty simple: moving water is cleaner because it’s often colder and it’s frequently in motion.

I knew that more bacteria often grow in warmer waters and that waters that are stagnant are more likely to warm up. Furthermore, many stagnant ponds simply look dirtier than their faster-moving counterparts.

But check this out. Last winter, I attended a lecture on Wilderness Medicine by Doctor Howard Donner of the Wilderness Medicine Institute. One of the topics the crowd was very interested in was water filtration.

Dr. Donner cited a recent water quality study throughout the Sierras that actually found the first 12 inches of lake water to contain fewer bacteria than moving streams, creeks, or rivers. But why? The theory that Dr. Donner shared with the crowd was quite simple.

The first 12 inches of standing lake water, because it’s mostly snow runoff in that area, is more subject to ultraviolet radiation than moving water. In essence, the same thing is happening to this standing lake water that many of us are doing to water in our bottles with common filtration devices like the SteriPen.

In addition, because lake water isn’t moving as much, the larger and heavier bacteria have more time to settle to the lower depths of the body of water. This is actually one of the reasons why Lake Tahoe is one of the cleanest, clearest lakes in the world.

So, the big takeaway here is, at least in the High Sierras, lakes may actually be better sources than streams or rivers, where potentially harmful bacteria are bouncing around at all depths.

With that said, in areas where lakes aren’t primarily filled with snow runoff and water clarity is less than 12 inches, I think it’s best to consult with local park rangers or forest service staff to learn about the best sources for clean water on the trail.

How Can You Ensure Safe Water Filtration?

There are a wide variety of water filtration techniques out there. I personally have the most experience with MSR hand-pump filtration systems, as well as the UV-reliant SteriPen. You can also purchase iodine tablets to pop into your water.

These require at least 30 minutes to kill any potential protozoa, bacteria, or viruses in the water. The downside of iodine is that some people don’t like the taste after that 30-minute waiting period is up, so you can use additional vitamin C or ascorbic acid tablets to improve the taste.

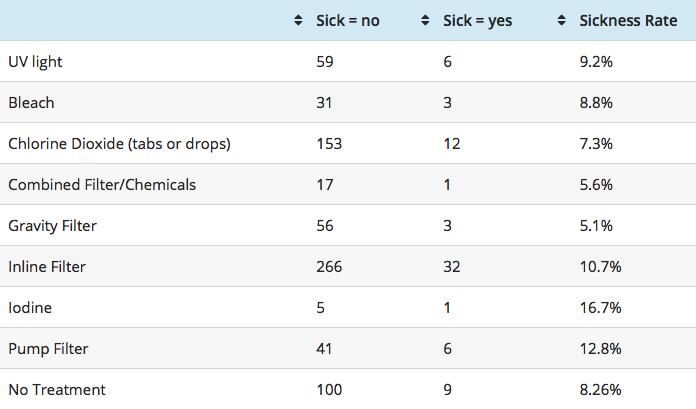

Overall, the types of filters and purification techniques out there are largely broken down into these distinctions: UV light filters, chemical purification (i.e. iodine, bleach, chlorine dioxide), pump filters, gravity filters, and inline filters.

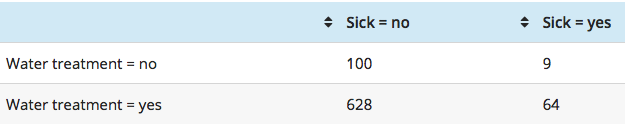

Of all these methods, this study showed gravity filters, such as the Sawyer System, to provide the lowest rates of users experiencing sickness after using them.

What Happens If You Don’t Use Safe Water Filtration?

There is no straightforward answer to this question, and more and more research is actually finding that there is relatively zero difference in sickness rates between backpackers who always filter their water and those who don’t. So, if you want to take your chances and reduce your pack weight by not carrying a filter, you’re a free human being and I won’t stop you!

But if you want to be safe instead of sorry, you’ll find a water filter that fits your needs. Many avid backpackers actually used a combined method, such as the SteriPen and iodine, to ensure clean drinking water. The bottom line is that the worse that can happen is you come down with one of those previously mentioned forms of protozoa, bacteria, or virus.

If you’re close to a trailhead, you’ll be able to walk out and deal with the symptoms from the comfort of your home, but on an extended backpacking trip, the loss of fluids that accompanies these bacteria can become a serious concern. That’s why, for me, it’s better to have a water filtration method (or multiple) than to simply leave things to chance!

What Method Do You Use for Safe Water Filtration?

At The Backpack Guide, I’m always looking for new trails and wildernesses to explore and I’m also interested in the experiences of others in the wild. I want to know which type of filtration method you prefer, why, and if you’ve ever had a harrowing experience related to water filtration in the backcountry.

Feel free to reach out to me directly (email below), or share your latest adventure or backpack by tagging @thebackpackguide on Instagram, Facebook, or Twitter!

I hope you’ve enjoyed this Backpacker’s Guide to Water Filtration and I’d love to hear your feedback in the comments section below. I’ll be quick to reply to any questions, comments, or concerns you feel like sharing!

Here’s to Filters, My Friends!

The Backpack Guide

Comments

Hi there Tucker,

Thank you kindly for this rather educational, factual and informative article regarding water filtration. It is truly appreciated. Thanks.

On the rare occasions that I do go trecking these days I am a stickler for making sure I have more than enough water with me. I also go through a pre treck routine for the previous 2/3 days making sure my body is well hydrated by taking 4.5 to 6 litres of fluids daily. My own theory is that if I am well stocked up internally with water I will need less when I am actually on the treck, and well with so much water and with each bottle I consume the treck only gets easier as the load gets lighter due to the reduced weight!.

I do carry Iodine tablets as an emergency back up, and thanks for the idea of using soluble vitamin C or multivitamin tablets to aid with the flavour.

I have medically dehydrated twice..I tell you it is no fun, a serious condition that requires hospital treatment!.

Author

Thanks Derek!

That little flavor boost is more for morale than anything else, but that goes a long way when you’re out for an extended period on the trail.

I’m glad you found this article useful!