Here we are in the Lake Tahoe Basin, carving alongside glacial valleys beside volcanoes. The geologic stories from the rim and canyons of the Lake Tahoe Basin are in motion, at times avalanching through canyons to gently settle in sky blue waters.

This is not a brochure to hastily summarize the geologic formation of Lake Tahoe but a collection of stories to instill informed adventure amongst the rocks and stones of the Lake Tahoe area.

From 20 kilometers beneath the granite, a path into the wilderness emerges and guides us into a story of the past. Part Two of the School of Stone submerges to an ancient time before the granite of the Sierra was even a twinkle in Earth’s eye; back to explore Tahoe’s tropical past.

Side note: If you missed the first installment of this two-part series, be sure to pop back and catch up on School of Stone Part One!

Article Overview

Uncovering Ancient Stories

As we explore the lush canyons and crumbling crags of the Tahoe area, we find pieces of a provoking puzzle. With our tools of storytelling and community, akin to those of a rock hammer that’s blunt on one end and sharp on the other, we uncover fresh surfaces.

We’ll ascend the layers of time to a cascade of stone where the old and the ancient mingle. This is an invitation to a trail where the stones beneath your hiker’s sole offer a story to ponder or share while you saunter the peaks and valleys of the Lake Tahoe Basin.

River Canyon Promenade

This story begins at the base of Ward Canyon, about a five-minute drive from Tahoe City south on Highway 89. On the west shore of Lake Tahoe, Ward Canyon cradles Ward Creek, which seasonally deposits the Sierra Crest snowmelt into the Lake.

This creek renders a space available for stones of old and ancient times to mingle. Rocks that are 300 million years old can be found smoothed by the flow of meltwater resting next to a rock that is 250 million years younger.

That is the nature of rivers: to carry and deposit rocks that are old next to rocks that are even older, bringing them to a commonplace.

But Ward Canyon is anything but common. It boasts striking views of Twin Peaks, a volcanic duo that sharply holds their place on the Sierra Crest, and north to Ward peak, a part of the legendary ski area known as Alpine Meadows.

Here in the lower region of Ward Canyon, the Tahoe Rim Trail dissects Ward Canyon Road and Ward Creek before ascending a moderate grade and linking up with the Pacific Crest Trail. This section of the Tahoe Rim Trail passes through magnificent old-growth forest and over stones that have stories worth sharing.

Leaving the car behind at the trailhead, we descend to Ward Creek. Not far down a small embankment of recent river deposits, we reach the braided riparian zone where the creek has slowed.

In the warm spring months when snowmelt is at its highest, the creek runs deeper and stronger, which makes crossing here at the Tahoe Rim Trail a process of negotiating a few braiding creeklets by way of log bridges.

River rocks, rounded by the river randomly jumbled, separate the few divided sections of the creek. Some of these stones are around 300 million years old, which makes them some of the oldest rocks in the Sierra Nevada.

From here, they seem quite content to rub shoulders with fellow stones that are more than 250 million years younger. What kinds of stories do you think these stones would share if they could speak?

Rising Tropical Stone

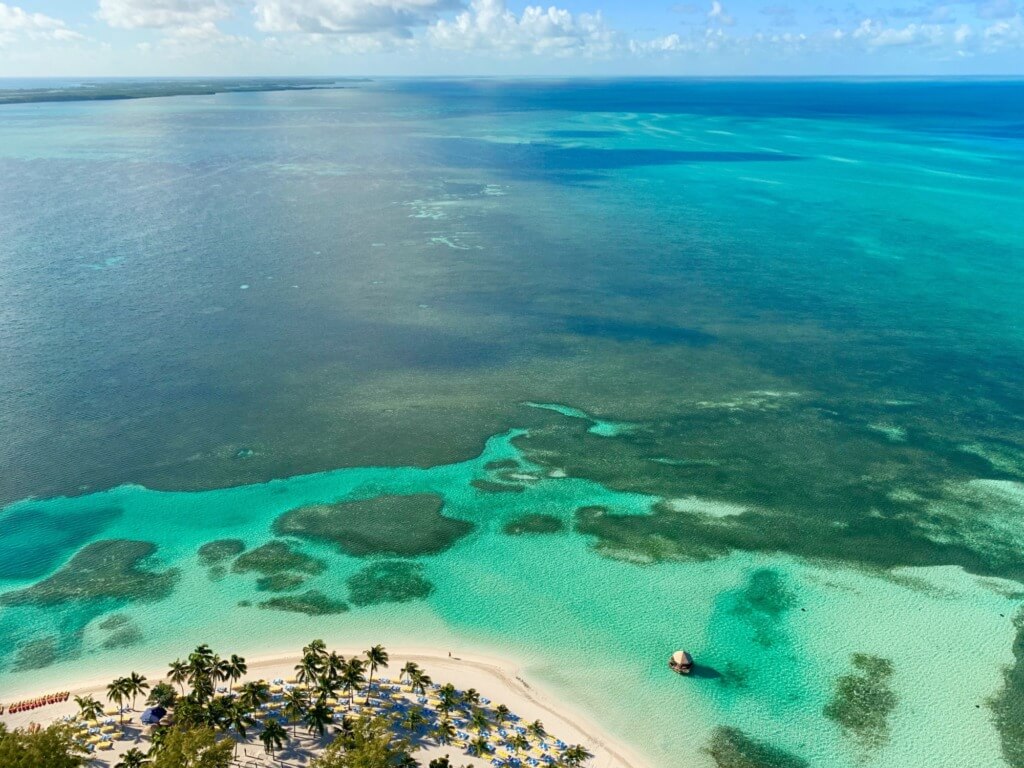

Imagine a shallow sea with light blue water. much like the Bahamas. We are 300 million years in the past and what is now California is covered with warm ocean water and sandy shores rimming small islands.

Let’s dive into deeper waters and descend to the bottom where we find a muddy sludge. Bust out your handy dandy microscope… and ah-ha! Radiolarians! Thriving in the ancient tropical sea, the radiolarians fall to the bottom when they die and stack upon the billions.

A few million years of these plankton shells stacking upon each other, the ones at the bottom become squished and compacted. Pressure from above adds a little heat and makes the sludge denser. When it dries, a fine stone is formed.

The Young Sierras

For roughly the next 200 million years, this solidified sludge (called ‘chert’) from the shallow ocean uplifts. It rises with the aspiring granite below to form the young Sierra Nevada range.

When our young range reaches a height of 8,000 feet, the icy grasp of glaciers arrives and begins grinding upon the solid, marine-derived stone. Breaking into smaller, denser stones, the chert rumbles down the upper reaches of Ward Canyon.

Moved by the effects of ice and spring snowmelt, the chert arrives at its lower resting place and nestles amongst the other rocks in Ward Creek. Year after year, the chert is lapped by the seasonal snowmelt then dried by the hot Sierra sun.

As we cross the small channels of Ward Creek on the Tahoe Rim Trail, we may find a piece of chert rambling on it’s 300 million year journey. It might feel like we couldn’t be further from the ocean, but these stones remind us of processes nearly as ancient as life itself.

Volcanic Rumbling

Rubbing shoulders with our planktonically-derived friend chert is another stony traveler that has a very different origin; that of fire and molten Earth. There have been many volcanoes in the story of the Lake Tahoe Basin.

Around 30 million years ago, the Sierra Nevada and California have risen from the tropical waters and North America has slowly made its way north. Latitudinally, we now reside much closer to our coordinates today, but an eruptive force is ripping through the Sierra crest.

The presence of silica in magma deep beneath our feet can make a volcano so explosive that it erupts and cascades small stones and even car-sized rocks in what is called a lahar flow. A kind of volcanic avalanche of hot ash and partially molten rock, a lahar is something you don’t want to be at the business end of.

Tumbling through the canyons of the past, these avalanches of volcanic ash forcefully ripped stones of all sizes from their resting places to become part of the volcanic cascade.

The steep walls of Ward Canyon are scoured as they direct and concentrate the tumbling volcanic mix. When the lahar flow finally settles lower in the canyon, the chaotic composition cools rapidly. This leaves a dense solidified debris composed of volcanic stones suspended by lithified ash.

Today, preparations for an epic powder day will bring the men and women of Alpine Meadows Ski Patrol to the top of Ward Canyon. Dynamite is used to trigger avalanches of snow down the same steep canyons that once directed avalanches of much hotter compositions.

Chaos in Solid Form

Through about 30 million years ago, these volcanic avalanches cascaded down Ward Canyon. They brought colossal pieces of molten rock downhill. But just as in any avalanche, these lahar flows solidify when stopped, often leaving behind a chaotic jumble of debris.

The hardened volcanic flow then becomes subject to the grinding grip of the glaciation, only to be found by the patient hand of water smoothing and depositing volcanic chunks of stone along the river banks.

For a present day example of one of these colossal chunks of volcanic material, let us head over to Eagle Rock. This one popular short hike on the West Shore offers a magnificent eagle’s eye view of Lake Tahoe.

It’s one of the best places on the lake to watch the sunrise over the Carson range and trickle early morning light onto a chilly Tahoe morning. It is also a noticeable landmark for anyone kayaking on the West Shore.

Just another five minutes south on Highway 89 south from Ward Canyon, Eagle Rock towers overhead. We park beneath the massive monolithic rock and ascend the trail, which meanders up the backside and emerges to a magnificent overlook of Lake Tahoe.

Although it’s rather steep, the trail is only about a half-mile long. As we hike, bring your eye up to the cliff’s side and notice its complexity. With volcanic chunks and pockets of varying sizes visible on the cliffside, Eagle Rock is a solidified cover page of Tahoe’s eruptive past.

Chunks of stone big and small were picked up in a cascading, eruptive flow and then suspended and solidified together in large form. At the base of Blackwood Canyon, Eagle Rock has been wedged by frost and scraped by glaciers.

The pockets we see today atop Eagle Rock tell of a weathered past. Similar to volcanic rocks found rimming the north and west reaches of the Lake Tahoe Basin, Eagle Rock is a dramatically placed and easily accessible volcanic showcase.

Layers of The Lake

Now let’s go to a beach on the north shore just under three miles north of Tahoe City on Highway 28. Skylandia Beach is a part of the California State Park system and a welcomed refuge for many visitors of the high Sierra sun in the hot summer months.

After the short walk down to the lake’s edge, we arrive at a well-formed beach with full east-to-west views of the Lake of The Sky. With our toes (or maybe more) dipped into Tahoe’s refreshing waters, we look back towards the cliff above the beach.

The layering of different sediments becomes especially apparent in the crumbly gravely cliff. The youngest of any rock thus far in our stories of stone, these crumbling, eroded cliffs above Skylandia Beach are lake deposits that are about 11 thousand years or younger.

During our most recent ice age, the Tioga, the canyons around Lake Tahoe were partially filled with serpents of ice slithering their gravity-powered path towards the lake.As days became warmer, the serpents of ice slowed and began to melt in place.

Despite gravity’s inevitability, their downhill progress was thwarted by climatic shift. All of the sand, gravel, and stones picked up by the ice becomes subject to this melting process.

Torrential rivers and whitewater pick up even more sediment before eventually reaching the lake and releasing everything they’ve picked up along the way. One melting flush and its sediments settle to the bottom near the gushing inlet at Skylandia. Then another and another, settling and compacting the layers beneath.

Rising Thaw

Glacial melt from a twilighting ice age replenishes the lake to a higher level than we see today. At one time, all of the popular beaches rimming Lake Tahoe were well underwater.

When the glacial ice has all but melted and the torrent is limited to seasonal snowmelt, the vast surface of the lake is subject to the evaporative force of the sun.

Day after day and year after year, this evaporative process lowers the water level and exposes the crumbly deposited cliff at Skylandia.

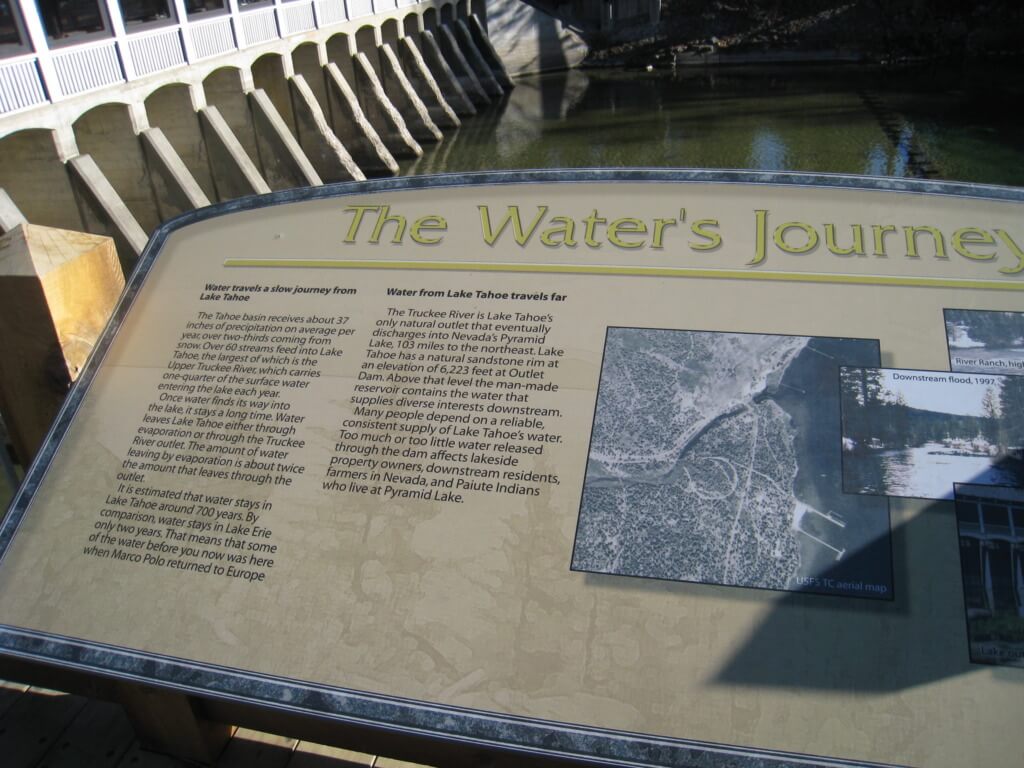

Today, it is said that more water evaporates off the 191-square mile surface of the lake every day than runs out of the lake via its only outlet in Tahoe City, the Truckee River.

Pieces of the Universal Puzzle

As we may see, the geologic stories we find in the Tahoe Area are pieces of a universal puzzle. Although we can find two stones lying next to each other on our hike up a snowmelt creek, their journeys to come to that point may be very different.

One once called the ocean home. Another erupted from the heat of a volcanic peak. But all help us tell the fascinating story of how the Lake Tahoe landscape came to be.

About The Author

With a Bachelor’s degree in Environmental Science and Biology from UC Santa Cruz, Eliot Headley seeks to share and further understand the natural world through adventurous experience. He lives and works in Lake Tahoe, California as a tour guide.

Comments

Wow! Such amazing pictures from River Canyon Promenade made really want to travel so soon just to see these Rocks that are 300 million years old!!! I’m not a biologist or geologist but I love nature. I don’t think I haven’t been so closed to a place with 300 million years rocks that could look so astonishing as in the River Canyon Promenade.

I enjoyed this article and learned so much about an area I love . Most of my geological studies were focus on the East coast with exception of Washington state . Thank you for sharing this article ! Geology is my love !

Thanks Mary!

I hope you’re staying well throughout this challenging time!